Welcome back to The Evolving Physio for a discussion of a cloudy subject where I will be discussing the do’s and probably do not’s of a classic shoulder pain favourite, sub-acromial pain.

Some of you may know exactly what this is and some of you may know this pleasantry of a condition by a more common term ‘SHOULDER IMPINGEMENT’ or ‘SUB-ACROMIAL IMPINGEMENT’ . Yes that ear piercing, distasteful, dreaded, frightful, cold sweat trickling, “yuck” of a term.

Before I get my feathers ruffled in this mess lets talk about what my concerns are with this condition and the clouds looming over it that make it that much more difficult to treat.

This topic will be diving into two problem areas for me with sub-acromial pain:

Poor terminology

1- Impingement Syndrome

Like a game of chinese whispers the older term ‘impingement’ has lingered and continues to spread in our profession in a more destructive than educational manner. Well im spreading the new whisper….stop calling it that!!

‘Impingement’ has created a wrongly painted image in the publics belief and the Picasso’s are a vast quantity of Dr’s, physio’s, other allied health or even Surgeons that I have come across that have failed to see the issue with the current. These are people the public hold in very high regard for telling them exactly what the issue is (particularly if they are skilled enough in the art of knife to skin). This is a term that likes to have patients shaking in their boots on the thought of putting their washing on the line. Don’t believe my word?? Have a listen to one of the experts and leaders in shoulders Dr Jeremy Lewis here

FEAR is a secondary side affect that can develop because of the way ‘impingement’ is described to patients. If we know ANYTHING about pain…. its that its purely the brains interpretation of damage or the threat of damage so we are not doing any favours putting the fear of god in these people and creating fear-avoidance and a psycho-somatic component to their presentation. Have a read of some brilliant content in this area of understanding pain here

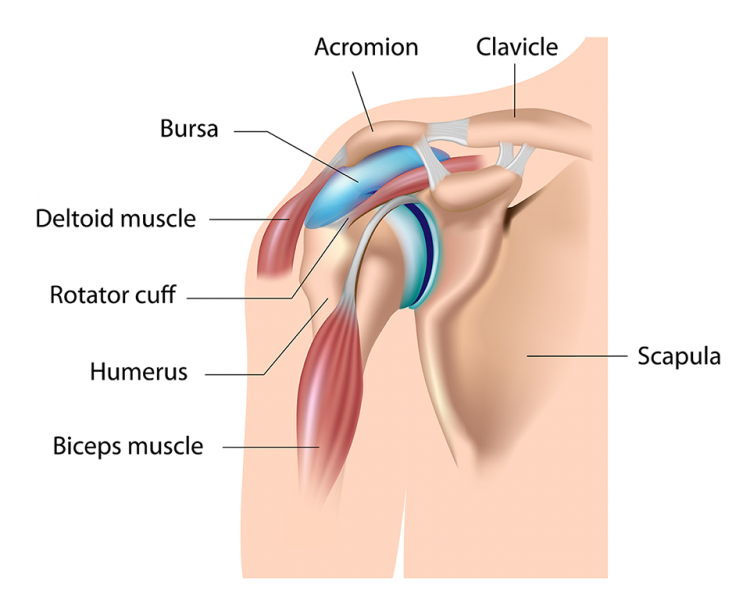

The second and most frustrating issue with this terminology is that it is simply wrong as a descriptive cause of pain when explaining pathology to a patient. An average person creates an ‘impingement’ like action between the acromion and the soft tissue structures lying between it and the humeral head as soon as you raise your arm. You are applying compressive forces for all structures residing in your sub-acromial space including the majority of your rotator cuff and sub-deltoid bursa. So to say that that action is the cause of pain and all our shoulder goodies are getting squished “abnormally” is just ridiculous. The acromial impingement model is an older theory that seems to have stuck around particularly with physiotherapists despite the lack of evidence for this theory. Newer theories however, seem to concentrate on other mechanisms as a likely cause. These include theories such as poor cuff control which causes superior translation of the humeral head under the acromial arch or poor scapula control. Now does that mean the compression under the acromial arch is the main issue or would we treat the cuff control to address the lack of stability and superior translation. This is the current dilemma with shoulder “impingements” and it is possibly why a lot of sub-acromial decompressive surgeries fail as they don’t necessarily address the cause of the pathology. There are exceptions you need to keep an eye on such as abnormal acromial types which don’t seem to have much success with conservative treatment.

One of my favourite explanations of the issues for this ‘impingement’ debacle comes from shoulder expert Adam Meakins in his blog ” Shoulder impingement…. some extra thoughts” on the sports physio here where he states:

“So if compression of these structures is a normal action why do we use it to explain to a patient why their shoulder hurts when they lift it up? We don’t tell people with knee pain when they squat that they are getting meniscal impingement do we, but this normal anatomical event happens every time you bend the knee, its only when the mensicus is damaged do they get pain, so we use more accurate descriptive terms like meniscal lesion, tear, degeneration etc, so why don’t we do this for the shoulder? Surely its obvious that it’s only when the sub acromial structures become pathological do we get shoulder pain, it’s not the impingement that causes pain”

This term is still used in my beliefs simply because it is easy. It is an easy way for patients to understand and an easy way for clinicians to explain. But as I have learnt if you want to do things the right way in health it isn’t the easy way. In our defence it is made hard enough for clinicians who have to work with unreliable current orthopaedic tests which make it next to impossible to accurately diagnose a shoulder pathology correctly. They also need to consider there are different types of “impingement” such as primary, secondary, internal and external which can be broken up even further into ‘impingement’ location. All of these require a different assessment and treatment approaches which makes it a whole detailed topic in itself for a different day to discuss.

Maybe I am a little bit harsh on it but in a world of health where subtle differences matter I believe its a more accurate and reliable term to umbrella it as a broader term put by Dr Lewis : Sub-acromial pain. This term is preferable as it eliminates any fear factor within the patient and allows for all types of shoulder pathology to fall within it which could be more accurately defined with further investigations of subjective and objective history.

2- Bursitis

My second issue is something a little left field and more of a personal vendetta. However, it does fall under shoulder miss-interpretation in my beliefs. Over the past few years I have noticed the high frequency of referrals for “burisits”. A lot of referrals from GP’s or even specialists come to me with the words bursitis scribbled on abit of paper. Now I have some issues with “bursitis”. Whilst I don’t argue you can get pure bursitis as an isolated issue with sub-acromial pain incidences and I am also aware of the high nociception in bursas that can cause this pain. I do however, argue that it is not even near as common as it is diagnosed. Lets put it under some scrutiny:

- Most of these patients have had an ultrasound and have a conclusive result showing “bursitis”. Yet what we know of imagery results is how little relevance it should have. If you scan the public you would find a huge percentage of us with ” Bursitis” or bursal thickening. In fact the most common finding in asymptomatic patients on scans is bursitis or bursal thickening. ‘Bursitis” simply means there is slightly more fluid than normal in our bursa or it has naturally thickened from trauma/adaptation or several other reasons. This is one of those frustrating imagery results that could well of been there before someone presents with acute shoulder pain. With no real cut off point between variation in bursa sizeing or fluid content within them and when someone labels it “bursitis” you can see the flaw with diagnosing someone with this pathology at this point in time.

Cause or Symptom ??? - The sub-acromial bursa is not quite the shape you think it is. The base of the sub-acromial bursa is really the top of the supraspinatus tendon. This means that it is really just an igloo ontop of the supraspinatus tendon. Any pathology in the shoulder is quite capable of causing a “increase in bursa fluid content”. It is because of this reason I theorize that a lot of these “Bursitis” diagnosis may well be insignificant or a secondary symptom.

I think the important thing to learn is that clinically we have to marry these up as a patient specific assessment. If I get a patient who has subjectively had a ” twinge” picking up a heavy object below shoulder height and their U/S says bursitis and no other significant findings I would take that information very lightly as a completely normal SYMPTOM (if relevant at all) after a recent event not necessarily a diagnosis as this could be a range of things including completely un-related issues such as neural like symptoms. So please don’t be so quick to slap bursitis as a diagnosis as with impingement, take your time to consider its relevance.

Summary

We must understand that terminology is an area that does constantly change in health. Whilst it may seem a insignificance at first it can create secondary issues with the patient and inaccuracy with treatment planning if we don’t fully understand the pathology at hand. Tendinopathies have changed from tendinitis or esis etc. because of the hard work of many researchers over the years which has lead to a greater understanding of the physiology of the condition. ‘Impingement’ is an area which I believe is slower to take on this next step and needs to be enforced more.

Shoulder pathologies can be in depth and vast in there presentations making them very hard to accurately diagnose. Understanding that the current tools we have are not completely accurate or may lack relevance, conducting a detailed history and good clinical reasoning skills are imperative tools for a therapist to create the most accurate hypothesis in shoulder presentations.

If your using the word impingement still…….please stop and don’t make me and many others try and unwind the mess it could cause for future treatments.

“Sub-acromial pain” is in my opinion the top descriptive term at this point in time.

P.S. If your interested in a good creative way to assess shoulders and better guide treatment the SSMP is a great tool invented by Dr Jeremy Lewis you can download here and find information on here

Dr Jeremy Lewis, Dr Chris Littlewood and Adam Meakins are great resources for shoulders if you wish to look into and understand shoulders further.

Until next-time,

Keep moving

Dale Hardes